Shane Howard of Goanna Discusses "Solid Rock," Spirit of Place, and More

A classic Australian rock album approaches its 40th birthday.

Thanks for spending part of your day with Michael’s Record Collection. I appreciate your time, so I want to let you know up front that this issue is rather long. It discusses an album and a song that I’m extremely passionate about, as well as the important event that led to their creation. I’ve separated it out into sections to make it easier to remember where you left off if you’d rather read it in chunks. My hope is that you’ll enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

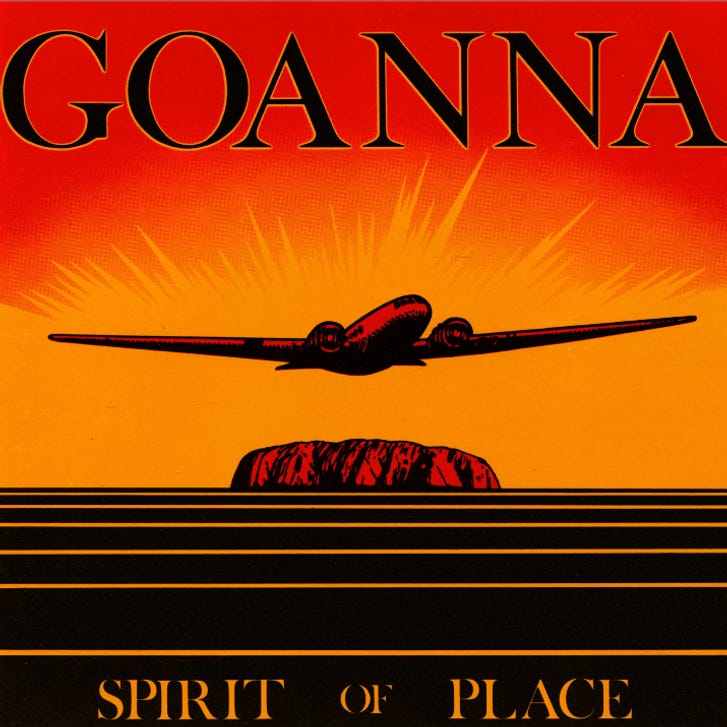

I recently had the pleasure of speaking with Shane Howard, who formerly fronted the Australian band Goanna from 1977 to the mid-1980s, and then again briefly for an album release in 1998. Shane told me about the genesis of one of my all-time favorite records and the band behind it. Spirit of Place, with its hit song “Solid Rock,” is one of the great records of the 1980s and it is a shame it’s not more widely known in the United States.

The Awakening

It’s been 40 years since Australian singer-songwriter Shane Howard went camping near Uluru (formerly called Ayers Rock) and underwent a self-described spiritual awakening. After seeing Indigenous Australians performing ancient dance rituals, Howard realized that they had a true connection to the land he had called home for the 20-odd years of his life to that point. It made him question his own connection to his homeland, and it made him rethink everything he knew about Australia and to whom that ancient land belonged.

In 1981, the pressures of the time and travel involved in Howard’s burgeoning rock music career had been colliding with the strain of caring for two small children in the house, and it was wearing him down. Getting home from a gig late at night and rising early to help with the children while his wife went off to work took its toll and started to affect his health.

“The doctor said to me, ‘Look, you’ve got to have a break,’” Howard said. “I’d always wanted to go to Uluru. I wanted to see, was Aboriginal culture still alive in this country? Did people still speak the language? Did people still dance the dances? Was that deep sense of culture still alive? It was a bit of a quest. It was a bit of a journey into the heart of the country. Now you can go to a four-star resort with a swimming pool, but back then you just camped wherever.”

While Howard was camping there, he came across some Aboriginal people from Amata and learned from a woman hanging a sign that there would be an Inmar — a traditional song and dance ceremony — on the other side of the rock at sunset. He walked about four kilometers to get there as the sun was sinking and found the dancers painted in a white ocher.

“They come into the firelight as darkness is falling and the light on the ocher makes them look like spirit figures, dancing. It was a powerful moment,” he said. “These are stories that are some of the oldest archetypes of human stories that we have in language, in song, that may have been sung like that for 10, 20, 30 thousand years or longer. And in that very moment, over the silhouetted form of Uluru in the background, the full moon came up.

“Now, I don't know if that was coincidental or good choreography, but it was one of those moments where I woke up, you know, and I went, ‘Wow, I am in someone else's country. And I don't know where I am. I'm not quite sure that the God of my ancestors holds any sway out here.’

“I saw something truly powerful and beautiful and really, really ancient. And once you know, you can’t un-know, and you can choose to look away or you have to push on through and deeper into that experience and I choose to push on through. And then my life changed.”

That epiphany led him to write the biggest hit song of his career and one of the greatest Australian pop-rock songs of all time, “Solid Rock.” Howard wrote the first lines and, in his words, started “mucking around with a guitar and the riff began to emerge.” The band’s biggest song came together quickly after that.

“At Uluru at that time, I was given those opening lines, and really the first verse, and even the beginnings of the second verse, and the riff,” Howard said. “And those things kind of came together in the space of a few days.”

The Backstory

The Goanna lineup that recorded the Spirit of Place album — which would include “Solid Rock” — rose from the ashes of an original four-piece band. With the help of Ian Lovell, a promoter running the Eureka Hotel in Geelong, Howard pulled together the band with which he wanted to surround himself.

“If you weren’t in Goanna, you weren’t anyone,” he said with a smile. “So, we kind of pulled this band together from the ashes of the first band. And we kind of handpicked a lot of the great musicians from around that area. Rose Bygrave was a beautiful keyboard player, beautiful singer, and songwriter. Marcia, my sister, who I was resistant to, initially. Ian wanted her in the band. She was my little sister — about five or six years younger. I didn’t want to bring her into this corrupt rock and roll music world. It was very unusual for an Australian band to have such a strong feminine presence. Great bass player (Peter Coughlan). Great drummer (Robbie Ross). The best we could find in that district.”

The band holed up in a two-story house that became known as Goanna Manor. Goanna converted a room into a rehearsal space and even printed their own posters there.

“We were fiercely independent,” Howard said. “We went out on the street and put our own posters up in the middle of the night on subway walls and what have you.”

It was an amazing time in Australia for music in the early 1980s. Bands were springing up everywhere and sending videos to MTV. All of them were working hard to be heard above the others in a place the size of the United States but with only a 15th of the population.

“There was this incredible cavalcade of bands traveling with six-man road crews and driving the length and breadth of the country and doing live shows,” Howard said. “They were really road savvy and well road-worn kind of bands. You’d be playing six nights a week and then traveling to the next place every day.”

The Hit Song

Goanna’s record company felt “Solid Rock” was too political to release as a single but Howard insisted that it should be the band’s first statement. And it worked. “Solid Rock” made it to No. 2 on the Kent Music Report in Australia and charted in the Billboard Top 100 in the U.S., though it never quite cracked the top 40 in this country.

The music video for “Solid Rock” got significant airplay on MTV and it was played on FM radio stations throughout the country. Spirit of Place (1982) was easily the best-selling album in Goanna’s brief existence — in no small part due to the anthem the band had recorded. If the title “Solid Rock” doesn’t ring a bell, maybe you’ll recall the video:

When I first heard “Solid Rock” on MTV in 1982, I immediately loved the riff, the Graham Davidge guitar solo (incredible, while not being overly flashy from a technical standpoint), and the excellent harmonies achieved by Howard, his sister Marcia, and Bygrave. I even loved the inclusion of the sound of Billy Cummins on the didgeridoo — an instrument that doesn’t often make its way into pop/rock songs. That was the first instance of a charted rock hit featuring the instrument, which gives the song an ominous and alien-sounding intro and jumps out of the speakers with animalistic sounds during a quiet middle section.

Being a bit of a sheltered kid in middle America at the time, I knew nothing of the plight of Australia’s native population or that country’s history of taking native children from their families and placing them with white foster parents. “Solid Rock” spoke to me on a social level, but not the way Howard intended. Instead, the imagery from Howard’s powerful writing hit me in terms of my own dawning awareness of the whitewashed education I had gotten regarding U.S. history and our own problematic treatment of Indigenous people.

They were standin’ on the shore one day

Saw the white sails in the sun

Wasn’t long before they felt the sting

White man, white law, white gun

That scene could have happened in any number of places and it certainly did so here.

Australian or American, it’s hard for anyone with empathy for other humans not to be moved by those words. In our school we were taught about the “warlike Indian” tribes and some of the battles and wars against them fought by colonial settlers. These were framed as necessary and heroic deeds, but history is always written by the winners.

I have no known historic connection to the people living on or colonizing this continent at the time of the European colonization of America — my father’s family arrived on these shores generations later and my mother was born in England and moved here as a child — but those lyrics still made me uneasy. How does one love his home when he knows the blood that was spilled and the people displaced to take it in the first place? Why does (or should?) a person feel guilt for actions that happened centuries before they were born and how do they express that feeling?

I didn’t know it then, but I was experiencing at least some of the same emotions and thoughts as Howard had recently had on the other side of the world. It was the first real connection I’d made to a social issue through the music I listened to, although I was somewhat missing his point. I was applying what he wrote about his country to my own. But it worked as a true-to-life analogy. When I learned that, it only served to make the song more powerful to me.

“Solid Rock” was always destined to capture my attention. I was a kid who hid shyness and introspection behind bluster and meager athletic talents that were never exceptional among my own age group. I was full of curiosity and wonder and had a vivid imagination and I leaned on those. I read. I wrote. I listened to music and looked wide-eyed at the record sleeves while devouring the lyrics. Even if “Solid Rock” hadn’t sucked me in with the strange noise of the didgeridoo and the catchy main guitar riff, Howard’s opening line immediately hooked me.

Out here nothing changes. Not in a hurry anyway.

What an incredible, yet simple, opening line. It immediately got me curious about where “out here” was. I didn’t find that out until years later, but that line stuck with me for life.

The Album

For a couple of years, the only Goanna song I’d heard was “Solid Rock,” which I’d recorded onto a cassette off of MTV. I picked up Spirit of Place on vinyl in my first year away at college and probably leaned far too heavily on the songs on Side 1. But the whole album is excellent.

Spirit of Place has much more to offer than “Solid Rock,” as good as that song is. Album opener “Cheatin’ Man” is a rocker and combines with “Solid Rock” to give the album a great one-two punch to start things off. The softer “Razor’s Edge” — written by Howard and Ian Morrison — reached No. 36 in Australia’s Kent Music Report. It didn’t dent the surface in the U.S., and the music video must have received very little support from MTV because I didn’t even know it had an official video until last week — and I’d wager quite a lot that I watched that channel as much as anyone humanly could.

Regardless, “Razor’s Edge” is a beautiful, acoustic, guitar-driven song perfectly suited for Howard’s voice and the excellent harmonies from his sister, Bygrave, and Morrison, with Bygrave also adding in subtle electric piano. But all the instrumentation works, with Ross and Coughlan laying down a solid foundation for the excellent guitar work of Graham Davidge and the late Ross Hannaford. The musicianship in Goanna was as good as, or better than, any of the Aussie bands that struck big in the U.S. and this song is a perfect example of that.

Here’s the no-budget video:

“Razor’s Edge” flows seamlessly into “Scenes (From an Occasional Window),” another mid-tempo, acoustic-driven song. In fact, they go together so well that listeners can be excused for not realizing one song has ended and another started. Together with “Razor’s Edge,” this two-song stretch more honestly reflects the folky, Americana style of music that Howard grew up loving (he says his biggest influence is Bob Dylan) — and later recorded on his solo albums — than the “rockier” tracks.

“My roots and Rose’s roots were really in folk music. But there was no room for folk music in the 80s,” Howard said with a laugh. “If you aren’t playing rock, don’t bother coming.”

Bygrave grabs the spotlight in “Stand Yr’ Ground,” taking a turn on lead vocals. Not quite as laid back as the previous two songs, and a bit less rock than the opening two, the song sort of “stands its (middle) ground” with a steady, driving bass line from Coughlan and some excellent saxophone from Joe Camilleri. Some fun hand claps must have made for enjoyable audience participation at those early 80s Goanna shows. The mood of the song belies the thoughts behind it.

“’Stand Yr’ Ground’ is a very working-class kind of perspective, but it also comes out of reading the works from Soviet writers like Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon, and (Alexander) Solzhenitsyn, you know, about the oppression and the gulags in communist Russia. Authoritarianism can come from anywhere.”

“Borderline” begins with lovely harmony vocals over an ocean sound and then builds into a faster-paced song that is poppy but doesn’t quite evolve into a full-blown rocker until past the halfway mark. If you’re not bobbing your head to the beat by the three-minute mark, please check your pulse to make sure your heart is still beating. Howard brings the song to a halt about half a minute after that and harmonizes with Marce and Rose again before the bouncy section kicks back in. It’s up near the top songs on the album for me.

The gorgeous “On the Platform” slows things to ballad pace. Along with a version of “Razor’s Edge,” the song was originally recorded on the band’s debut EP, when the group was known as The Goanna Band. Bygrave takes center stage again and she is credited as the writer. Her piano work is excellent, and we get an understated yet perfectly played guitar solo from Davidge.

The album builds back up slowly, starting with a soft, acoustic introduction to “Four Weeks Gone.” The longest track on the album (at 5:47), “Four Weeks Gone” again shows off Goanna’s vocal harmonies augmenting Howard’s earnest lead voice. The song builds in tempo and intensity, with Bygrave’s sparkling keyboards lending texture. Much like “Borderline,” “Four Weeks Gone” goes through some twists and turns, but it really starts to rock just shy of the four-and-a-half-minute mark. The lead guitar solo is scorching hot, but it’s low enough in the mix to allow everyone else to shine.

“Factory Man” is another mid-tempo acoustic number with a foundation of bass and drums so solid that you can’t help but nod along with it. It’s a little more country-rock than other songs on the album.

“(“Factory Man”) could be on the first Eagles album,” Howard said. “’Peaceful, Easy Feeling’ or those kinds of influences. I love those first two Eagles albums.”

“Children of the Southern Land” is a pro-Australian anthem that warns of the danger of giving up national identity chasing a culture more like ours in the U.S. It is the second-most distinctly Australian song, behind “Solid Rock.” It builds into a nice rock track with a soaring guitar solo.

“’Children of the Southern Land’ is a song that really rocks,” Howard said. “That’s a great song to play live. It’s a bit epic. ‘Children of the Sun’ is still resonating for me now and I’ve started playing it (live) again.”

Despite the obvious quality of the album, Spirit of Place didn’t make Goanna a household name in the U.S. like the band’s Australian peers of the time — Men at Work, INXS, and Midnight Oil, among many others. Even bands like the Divinyls, Moving Pictures, and Icehouse seemed to get more traction here at a time when Goanna was conquering Australia with their unlikely first hit single. It was largely down to nothing more than a miscalculation for demand and bad timing.

“Spirit of Place was that close really in America to breaking through,” Howard said, holding his forefinger and thumb about an inch apart. “There were a few quirks of history happening there. The record label we had in America through the Warner network — Warner Electra Atlantic — was actually Atco, which was the Rolling Stones’ label through Atlantic in America. If memory serves, what happened was they put it out to radio. It was considered a very political song. It was considered a very Australian song. I don’t think they thought it would do very well in the States.

“It had massive add-ons, over 200 stations in the first week, and then another additional 150 to 160 stations in the second week and it was going gangbusters. But they had not pressed enough stock — vinyl singles we’re talking about there. They didn’t anticipate that response. So, by the time they did manufacture (enough singles, which took about six weeks), the momentum was lost, and that little window of opportunity had passed.”

The Aftermath

Goanna followed Spirit of Place with Oceania in 1985. That album, which seemed more rooted in 80s pop sound, went gold and peaked at No. 29 in Australia per the Kent Music Report. The band turned to Little Feat keyboardist Billy Payne to produce after Dire Straits front man Mark Knopfler became unavailable due to another commitment. It’s got different tones and textures than Spirit of Place, but it’s another solid album.

The band broke up shortly after Oceania, and Howard embarked on a solo career, playing music that had much more in common with the works of Dylan than anything he had recorded with Goanna. He did briefly get Goanna back together for Spirit Returns (1998). The lineup bore little resemblance to the former band, but the core of Shane, Marce, and Rose is there. Spirit Returns has little connective tissue musically with Spirit of Place, as it is more representative of Howard’s folk musical influences, has more native Australian influence, and the core of the band had matured and become more sophisticated at that point in their lives. But one thing that didn’t change was the incredible way the voices of the two Howard siblings and Bygrave’s meld together.

Howard, now 66, has gone on to release 14 solo albums so far, including 2020’s Dark Matter. Already an author of two books, he is writing his memoir, which I eagerly await, but it may not be finished for some time, with all of life’s more immediate tasks often getting in the way. He’s led an interesting and admirable life, championing ecological causes in Australia — including writing and releasing a great song called “Let the Franklin Flow,” which is available on the reissue of Spirit of Place. He also supports the call for nuclear disarmament. His work as a champion for Aboriginal reconciliation and Indigenous Australian artists is too vast to fully recount here. He’s written hit songs for Irish singer Mary Black, serves on the Honorary Council of the San Francisco World Music Festival, and is a Member of the Order of Australia for significant service to the performing arts.

But has life gotten any better for the Indigenous tribes in Australia in the 40 years since the spiritual awakening that led to Howard’s best-selling song and album?

“Yeah, I can faithfully say it has,” Howard said. “Was it too slow? Yes, it was. Did I think change would be quicker? Yes, I did. That was youthful optimism. By the time we got to Oceania, I had a feeling that the dice was loaded, and the cards were stacked, and that there are very powerful and wealthy forces in this world who are keen to maintain the status quo.

“Then, by the time we got to Spirit Returns, which was a reunion album in 1998, 15 years later or whatever, I felt powerfully again that we were on the right track, and you’ve got to keep fighting hard for these things, like environment and like social justice issues. We’ve come a long way. Aboriginal people are much better off than they were. Is there further to go? Yes, there is.

“In the state of Victoria, they’re on the pathway to a journey of truth telling and there’s a commission for truth and justice on the journey to establishing a treaty with the first nations people. Now, we all know from the American and Canadian experience that treaties can be broken. Aboriginal people are not too optimistic about what treaties might deliver. But I think one of the really important things is the truth telling. That’s the part that hurts us as white fellas, because we don’t want to hear that our history was lesser than noble — that there are some deep scars in the landscape. But the old saying (goes) the truth will set you free, so let’s dig into the pain and let’s work our way through it. If we can do that, we can get out the other side and I think we can be a much more cohesive nation that is reconciled with its ugly history. You can build a proper national narrative from that.”

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for reading and I hope you check out Spirit of Place on Spotify or whatever streaming service you have (or just buy it on my recommendation, because it’s fantastic). This piece is, admittedly, a bit self-indulgent and could perhaps be more concise. The thing is…I could talk about Spirit of Place and “Solid Rock” for days. As much as I’ve written, my conversation with Shane went into much more detail. I invite you to watch the full interview below (our conversation actually went on another 10-15 minutes after I stopped recording), and please pardon the occasional lag and the fact that the video looks like he’s coming live from the international space station. Australia is, after all, half a world away.

And be sure to check out Shane’s website and the official Goanna website.

I’ve already got some exciting interviews completed for upcoming issues and I can’t wait to bring you those stories. Please feel free to share this issue or any of my previous posts with friends and family or boost the signal on your social media channels.